Can a Bee-Sized Brain Play Chess? Training a 1M Parameter Chess Engine ♟️🐝

An investigation into how a honey bee-sized neural network learns to play chess through next-token prediction

- TL;DR

- The Challenge: Chess as a Language Problem

- Model Architecture: A Minimal GPT

- Training Setup

- Evaluation: How Well Does It Play?

- Deep Dive: Multi-Token Move Architecture

- The Color Token Mystery: Shortcut Learning

- Visualization: Seeing What the Model Sees

- Tactical Awareness: Mate-in-1 Tests

- Opening Repertoire Analysis

- Where the Model Fails: Limitations

- Key Takeaways: What Did We Learn?

- Future Directions

- Conclusion: Can a Bee Play Chess?

TL;DR

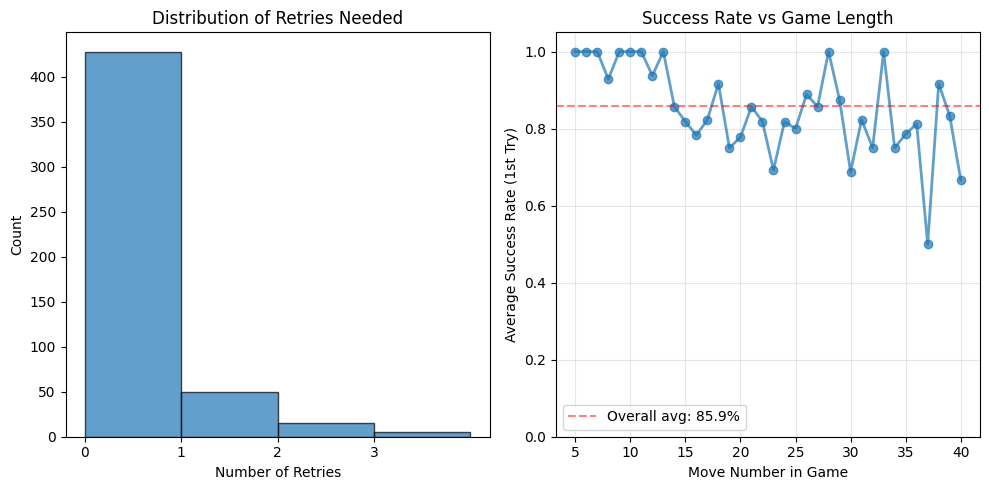

I trained a 900K parameter transformer to play chess using only next-token prediction - no explicit rules, no search algorithms, just pattern recognition. The model achieves an 85.9% legal move rate on first try, rising to 99.0% with retries. Here are some of the parts I explore in detail in this write-up:

- By training to predict the next token (actually 5 tokens per move: separator + color + piece type + from_square + to_square), the model achieves excellent legal move rates. One of the things I love about machine learning is how the training phase lets you ingest massive amounts of data, and complex rules emerge naturally from the patterns!

- Token 3 (piece type) is where real chess decisions happen (~57% confidence)

- The model uses shortcut learning for simple patterns (e.g., alternating colors)

- It excels at pattern matching but struggles with deep tactical calculations

This post documents the details of what the model learned and where it falls short.

The Challenge: Chess as a Language Problem

Context: This project was part of the 2026 LLM Course taught by Nathanaël Fijalkow and Marc Lelarge. Thank you for this fun project!

Why <1M Parameters?

The challenge was simple: train the best chess-playing language model possible with fewer than 1,000,000 parameters - roughly the neuron count of a honey bee 🐝. This constraint forces you to make every parameter count.

The Approach: Chess is Just Text

Instead of treating chess as a game with explicit rules and search trees (like AlphaZero), I treated it as a language modeling problem:

Input: [BOS] WPe2e4 BPe7e5 WNg1f3 ...

Output: BNb8c6 ← model predicts next move

Each move is encoded this way: WPe2e4 = White Pawn from e2 to e4. The model learns by predicting the next token, just like GPT learns to predict the next word.

Model Architecture: A Minimal GPT

The Final Configuration

After experimenting with different architectures, here’s what the configuration I used to stay under the 1M parameter budget:

ChessForCausalLM(

vocab_size=113, # Custom tokenizer vocabulary

n_embd=128, # Embedding dimension

n_layer=6, # Transformer layers

n_head=4, # Attention heads (32 dims each)

n_ctx=256, # Context length (tokens)

n_inner=384, # FFN inner dim (3× instead of 4×)

tie_weights=True, # Weight tying saves ~150K params

)

ChessForCausalLM(

(wte): Embedding(113, 128)

(wpe): Embedding(256, 128)

(drop): Dropout(p=0.1, inplace=False)

(h): ModuleList(

(0-4): 5 x TransformerBlock(

(ln_1): LayerNorm((128,), eps=1e-05, elementwise_affine=True)

(attn): MultiHeadAttention(

(c_attn): Linear(in_features=128, out_features=384, bias=True)

(c_proj): Linear(in_features=128, out_features=128, bias=True)

(dropout): Dropout(p=0.1, inplace=False)

)

(ln_2): LayerNorm((128,), eps=1e-05, elementwise_affine=True)

(mlp): FeedForward(

(c_fc): Linear(in_features=128, out_features=384, bias=True)

(c_proj): Linear(in_features=384, out_features=128, bias=True)

(dropout): Dropout(p=0.1, inplace=False)

)

)

)

(ln_f): LayerNorm((128,), eps=1e-05, elementwise_affine=True)

(lm_head): Linear(in_features=128, out_features=113, bias=False)

)

Total Parameters: ~900,000

Custom Tokenizer Design

I designed a custom tokenizer specifically for chess moves with a vocabulary of 113 tokens:

- Special tokens:

[PAD],[BOS],[EOS],[UNK],[SEP] - Colors:

W(White),B(Black) - Pieces:

P,N,B,R,Q,K - Squares: All 64 squares (

a1-h8) as single tokens - Modifiers:

x(capture),+(check),*(checkmate),o/O(castling)

This tokenization makes each move exactly 5 tokens: separator → color → piece → from_square → to_square. The compact vocabulary keeps the embedding layer small while making moves semantically structured.

Using the full move as a single token is another option that would have made investigating the model’s predictions much easier. However, the vocabulary can’t feasibly represent every possible chess move. While using only the most frequent moves is an option, it would fail to represent many valid games.

Training Setup

Dataset: 1M Lichess Games by David Louapre

dataset: dlouapre/lichess_2025-01_1M

format: WPe2e4 BPe7e5 WNg1f3 BNb8c6 WFc4 ...

split: 1,000,000 games

Each game is one long sequence of space-separated moves. The model learns by predicting each token given all previous tokens (causal language modeling).

Training Configuration

python -m src.train \

--output_dir ./my_model \

--num_train_epochs 3 \

--per_device_train_batch_size 16 \

--gradient_accumulation_steps 4 \

--learning_rate 5e-4 \

--warmup_steps 500 \

--max_length 256

Hardware: MacBook Pro M1 (32GB RAM, MPS acceleration)

Training Time: ~2 hours for 3 epochs

Evaluation: How Well Does It Play?

Legal Move Generation: 85.9% First-Try Success

The primary test: Can the model generate legal chess moves?

# Evaluate on 500 random positions

evaluator.evaluate_legal_moves(n_positions=500, temperature=0.8, seed=42)

Results:

Positions tested: 500

Legal (1st try): 429 (85.9%)

Legal (with retry): 495 (99.0%)

Always illegal: 5 (1.0%)

Key Finding: The model is remarkably good at generating legal moves! With a simple retry mechanism (sample 3 times), it achieves 99% success.

The left panel below shows the distribution of retries needed across all test positions. The right panel reveals an interesting pattern: as games progress, the model requires more attempts to generate legal moves, suggesting increased difficulty with longer game contexts.

Figure: Distribution of retries needed and Success Rate vs Game Length

Deep Dive: Multi-Token Move Architecture

Moves Are Composed of 5 Tokens

This is where things get interesting. Each move isn’t a single token - it’s built from 5 tokens:

Example: Black knight from b8 to c6

Token 1: " " (separator) → ~100% confidence

Token 2: "B" (Black to play) → ~100% confidence

Token 3: "N" (knight piece) → ~57% confidence

Token 4: "b8" (from square) → varies

Token 5: "c6" (to square) → varies

Note: The vocabulary includes all 64 squares (a1-h8) as single tokens, so squares aren’t split into separate characters.

Token 3 is Where the Piece Selection Happens

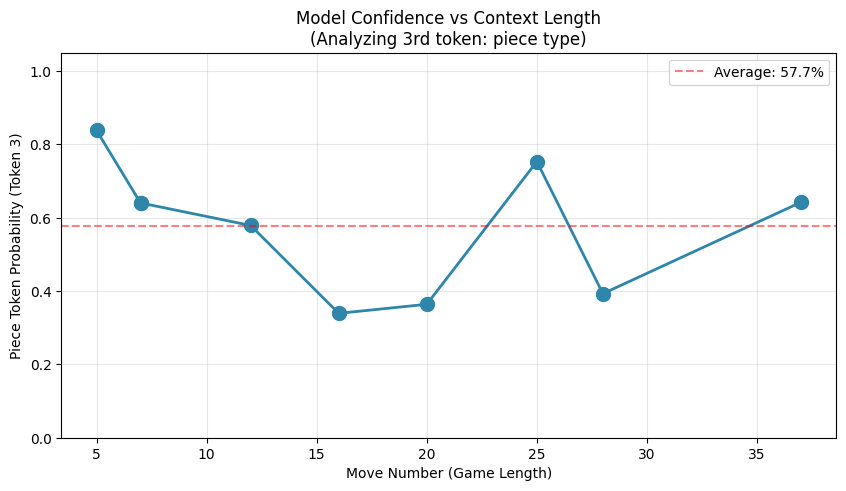

I analyzed the confidence at each token position:

def get_token_probs_at_positions(board, moves_str, num_tokens=5):

"""Get probabilities for all 5 tokens of next move."""

# ... generate tokens one by one, measure confidence

Findings:

- Token 1 (separator): ~100% - trivially predictable

- Token 2 (color W/B): ~100% - deterministic (whose turn)

- Token 3 (piece type): ~57% confidence - THIS is the chess decision!

- Token 4 (from square): Varies based on piece chosen

- Token 5 (to square): Varies based on position and tactics

Figure: Model’s confidence on piece type prediction (Token 3) remains stable across different game lengths

Why ~57% is Good News

The ~57% confidence on piece selection shows the model is genuinely uncertain about which piece to move. This is desirable! It means:

- The model considers multiple valid options (pawn vs knight vs bishop)

- It’s not overconfident

- The probability distribution reflects real strategic choices

Example: What the Model Considers

Position after e2e4 e7e5 g1f3 b8c6 (White to play):

Model's piece type probabilities (Token 3):

1. P 41.2% ✓ ← Pawn move (most common)

2. N 32.1% ✓ ← Knight move

3. B 18.5% ✓ ← Bishop move

4. Q 4.8% ✓ ← Queen move (rare at move 4)

5. K 2.1% ✓ ← King move (castling)

6. R 1.3% ✓ ← Rook move (hard to develop)

Interpretation: Moderate uncertainty (good!)

The model has learned that in the opening, pawns and knights are most likely to move, while queens and rooks are rarer. This matches chess principles!

The Color Token Mystery: Shortcut Learning

100% Accuracy on Predicting Color

Token 2 (W or B) is predicted with near-perfect accuracy. But how does the model do this?

I have run some tests to probe the behavior:

Investigation: 5 Tests

I designed tests to probe how the model predicts color:

Test 1: Normal Case (Move 4)

board = chess.Board()

board.push_uci("e2e4") # White

board.push_uci("e7e5") # Black

board.push_uci("g1f3") # White

# Model should predict: Black

Result: Predicted 'B' with 99.8% confidence ✓

Test 2: Edge Case (Move 1)

board = chess.Board() # Empty board

# Model should predict: White

Result: Predicted 'W' with 99.9% confidence ✓

Insight: Model learned that [BOS] → separator → 'W' is the starting pattern!

Test 3: Adversarial (Corrupt Last Color)

# Change last move from "WN..." to "BN..." (wrong color)

# Original: ...WPe2e4 BPe7e5 WNg1f3 BNb8c6

# Corrupted: ...WPe2e4 BPe7e5 WNg1f3 WNb8c6

# (Changed last move's color to confuse the model)

# Position: 4 moves

# Actual turn: White

# Expected token: W

# Top 2 Token 2 predictions:

# 1. 'W' 100.00% ✓✓✓

# 2. 'B' 0.00%

Result: Predicted 'W' - Model seems unbothered by the corruption

Test 4: Adversarial (Corrupt Last Color)

# Original: ...WPe2e4 BPe7e5 WPd2d4

# Corrupted: ...WPe2e4 BPe7e5 BPd2d4

# (Changed last move's color to confuse the model)

# Position: 3 moves

# Actual turn: Black

# Expected token: B

# Top 2 Token 2 predictions:

# 1. 'B' 100.00% ✓✓✓

# 2. 'W' 0.00%

Result: Predicted 'B' - Model seems unbothered by the corruption

Conclusion: In both adversarial cases, the model correctly predicted the right color to play. My hypothesis is that the model learns to play White on odd turns (1, 3, 5, …) and Black on even turns (2, 4, 6, …). This behavior would require deeper investigation.

Visualization: Seeing What the Model Sees

Example 1: Successful First-Try Move

Position: After WNg1h3 BPd7d6 WPf2f3 BBc8g4 WRh1g1 BPh7h5 WRg1h1 BPa7a6 WPd2d4 BNg8h6 WPd4d5 BBg4f5, White to play

Figure: Model successfully predicts Bishop development (green arrow)

Model's prediction: c2c4 (Pawn move)

Legal: ✓ Yes

Retries needed: 0

Analysis: The model correctly chose to develop the bishop, a classical opening principle!

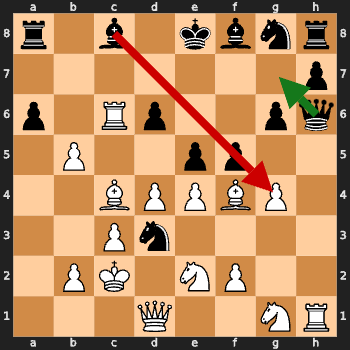

Example 2: Failed First Attempt (Red + Green Arrows)

Position: Complex middlegame after 18 moves

Figure: Red arrow shows illegal first attempt, green arrow shows successful retry

First attempt: Ne8f6 (White Bishop checks so Knight move is illegal)

Final move: Kd6c7 (Black king avoids the check)

Retries needed: 1

Analysis: Model missed the check position

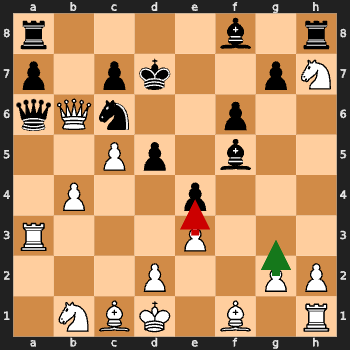

Tactical Awareness: Mate-in-1 Tests

I tested the model on classic mate-in-1 positions.

Challenge: Can you spot the checkmate in one move? 🤔

The green arrow shows the model’s move (spoiler: none of them are correct!).

Insight: The model missed these mate-in-1 situations. Training was not goal oriented so this was expected.

Opening Repertoire Analysis

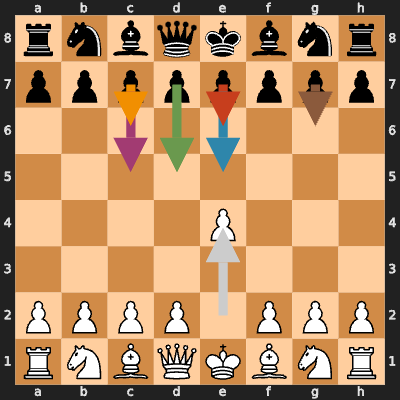

White’s First Move (100 trials)

first_moves = {}

for trial in range(100):

board = chess.Board()

move = model.generate_move(board, temperature=0.8)

first_moves[move] += 1

Results:

e2e4 46% ← King's Pawn Opening (most popular)

d2d4 28% ← Queen's Pawn Opening

g1f3 12% ← Réti Opening

c2c4 8% ← English Opening

e2e3 6% ← Other

Figure: Top 5 first moves for White, shown as colored arrows on the starting position

Analysis: The model learned the frequency distribution of openings in the training data! It plays e2e4 most often because that’s what humans play most often.

Black’s Response to 1.e4 (100 trials)

e7e5 52% ← King's Pawn Game (symmetrical)

c7c5 31% ← Sicilian Defense (sharp!)

e7e6 9% ← French Defense

c7c6 5% ← Caro-Kann Defense

d7d5 3% ← Scandinavian Defense

Figure: Black’s most common responses to 1.e4, with White’s first move shown in gray

Insight: The model has a reasonable opening repertoire dominated by popular defenses. The Sicilian Defense (c7c5) at 31% shows it learned aggressive play!

Where the Model Fails: Limitations

Common Failure Modes

Before discussing the theoretical limitations, let’s see some actual examples of where the model makes mistakes:

Example 1: Trying to Jump Over Pawns

The model sometimes forgets knights are the only pieces that can jump over others

Example 2: Moving Pawns Backwards

Pawns can only move forward - but the model occasionally tries backward moves

Example 3: Missing Opponent Checks

The model doesn’t always track which squares are under attack

These real examples show the model’s pattern-matching approach breaks down when positions deviate from common patterns.

No Deep Calculation

The model can’t think ahead. It predicts the next token based on patterns, not by searching future positions. This means:

- ❌ Can’t reliably find forced mates beyond simple patterns

- ❌ Misses long tactical sequences

- ❌ No understanding of threats or defensive moves

Limited Board State Tracking

With 256 token context and ~900K parameters, the model has limited “memory”:

- ❌ May forget piece positions in complex games

- ❌ Struggles with rare piece configurations

- ❌ Better at openings (memorized) than endgames (novel)

No Strategic Understanding

The model generates legal moves but doesn’t understand:

- Position evaluation (is this move good or bad?)

- Plans (pawn storm, minority attack, etc.)

- Compensation (sacrificing material for tempo/position)

It’s pattern matching, not “thinking” about chess.

Key Takeaways: What Did We Learn?

Language Modeling Principles Work for Games

Next-token prediction naturally captures sequential game logic:

- ✓ The model learned chess rules implicitly from data

- ✓ No explicit rule engine needed

- ✓ Attention mechanism handles move dependencies

Small Models Can Be Surprisingly Capable

With <1M parameters (honey bee-sized brain):

- ✓ 85.9% legal move accuracy

- ✓ Reasonable opening repertoire

This suggests efficient compression of chess knowledge is possible.

Multi-Token Architecture Provides Interpretability

Breaking moves into 4-5 tokens reveals:

- Where decisions happen: Token 3 (piece type)

- What the model considers: Probability distributions over pieces

- Confidence levels: ~57% means genuine uncertainty

We can see the model’s thought process at each token!

Pattern Recognition ≠ Understanding

High legal move rate ≠ good chess play:

- Model excels at learned patterns

- Struggles with novel positions requiring calculation

- Uses shortcuts (color flipping) instead of deep reasoning

This is the difference between System 1 (fast, intuitive) and System 2 (slow, deliberate) thinking.

Future Directions

Immediate Improvements

Scale Up

Curriculum Learning

- Start with simple puzzles (mate-in-1)

- Gradually increase difficulty

- Fine-tune on tactical pattern datasets

Hybrid Approaches

- Combine LM generation with shallow search (depth 1-2)

- Use model probabilities to guide MCTS

- Best of both worlds: pattern recognition + calculation

Research Questions

Scaling Laws for Chess

- 10M parameters → 2000 ELO?

- What’s the minimal architecture for 90%+ legal rate?

Comparison to Value-Function Approaches

- AlphaZero style: value network + search

- Pure LM approach: next-token prediction

- Which is more parameter-efficient?

Transfer Learning

- Pre-train on chess puzzles

- Fine-tune on full games

- Does tactical training improve strategic play?

Explore the Jupyter Notebook

jupyter notebook play.ipynb

The notebook contains all the analysis from this post: token probability analysis, attention visualization, mate-in-1 tests, and more!

Conclusion: Can a Bee Play Chess?

Yes - if by “play chess” you mean “generate legal moves 86% of the time.”

No - if you expect strategic understanding or deep tactical calculation.

The sub-1M parameter transformer learned impressive chess patterns through pure next-token prediction:

- ✅ Implicit rule learning from data

- ✅ Compositional move generation

- ✅ Reasonable opening knowledge

- ✅ Simple tactical recognition

But it lacks:

- ❌ Deep calculation abilities

- ❌ Strategic planning

- ❌ True understanding of positions

For a model with fewer parameters than a honey bee’s brain, playing legal chess 86% of the time is remarkable. The question is: can we teach this bee to sting? 🐝♟️

Published: February 2026